Posted on: http://www.israelhayom.com

By: Dror Eydar

June 2, 2017

Stop the occupation (of the mind)

The “land for peace” idea that has dominated diplomatic efforts to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for years fails to address the actual challenges posed by reality • Fifty years after the Six-Day War, here are 10 thoughts on those six days.

1.

Fifty years after the Six-Day War, we should know by now that the local Arabs never accepted the fact that dividing the land would mean that the Jews would also have their own state on land that was sanctified by Muslims. Over the last century, starting with the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement (a short-lived agreement for cooperation on the development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine and an Arab nation in a large part of the Middle East) in 1919, they consistently rejected land division proposals, thereby indicating their viewpoint on the matter.

Did the Palestinian majority in Jordan ever rise up against the Hashemite “occupation” and seek to establish a state there? Why didn’t the Arab residents of Judea and Samaria demand an independent state until 1967? The permanent rejection of partition plans, the rejection of Jewish history and the fabrication of an alternative history, the alliance with Islamist factions and the fact that the demand for an independent state was only ever made under Israeli rule, all these prove that all the region’s Arabs — from Hamas in Gaza, through Fatah in Ramallah, to Israel’s Arab citizens — have gathered around one core nucleus: Denying the Jews’ national identity and their right to a state of their own. It is not just the Hamas charter that denies our right to exist as Jews on this planet — the Palestinian National Covenant specifically states that “Judaism, in its character as a religion of revelation, is not a nationality with an independent existence” (Article 20). As such, we have no right to characterize ourselves as a people and we certainly don’t deserve a state.

2.

This has only been compounded by the general disintegration of states in the region. After World War I, the colonialist powers imposed their Western national definitions on the region — definitions that were foreign to the Middle East’s ethos, religion, culture and mythology. They forced a thin, modern stopper into the mouth of this enormous volcano of a region and hoped to keep the perceptions, values, views and beliefs that had governed it for thousands of years bottled up inside. But the lava forced its way out less than a century later, with tribes, clans and families emerging in defiance of the borders demarcated by the West. In retrospect, we now know that under the Western façade, ancient patterns always influenced the way the region behaved

.

What is Syria? A grouping of historically different social and ethnic groups and hostile tribes. What is Libya? Two enemy tribes artificially pasted together. What is Iraq? Sunnis, Shiites and Kurds with distinctive, hostile viewpoints. What is Lebanon? Sunnis, Shiites, Druze and Maronite Christians who never saw themselves as one nation. So how are the Arabs of the land of Israel different from the Arabs of Libya or Lebanon? What connects the Arabs of Nablus to the Arabs of Hebron — other than the express desire to undo the Jewish rule over this land?

3.

The concessions that Israel has offered in the name of peace, or a diplomatic arrangement, are well documented. There is an saying in Israel that “everybody knows what a future agreement will include.” The concessions that fall under this adage are: a withdrawal to the 1967 borders with land swaps and annexation of the large settlement blocs to Israel; a division of Jerusalem; and a limited right of return for Palestinian refugees, more or less. Everybody knows, that is, except for the Palestinians. They have never made any serious proposal that, in their view, would permanently end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and preclude any future demands. There is no such proposal. There is no Palestinian vision that includes a Jewish state anywhere in this land. There never was.

Let us try little exercise: Assuming that all this land, from the sea to the Jordan River, is declared Palestinian and belongs to Arabs, can anyone imagine an Arab or Muslim leader anywhere in this world who would be willing to recognize even one Jewish neighborhood in Tel Aviv? Would any Arab leader be willing to acknowledge the Jews’ historic, religious and legal right to, not all of the country, not even half of the country, but just this one single neighborhood? Not de facto, but de jure? Publicly, in the presence of their clerics and political leadership? Any volunteers? There’s the root of our self-deception.

4.

Fifty years later, we are stuck in one psycho-political fixation made up of one paradigm with many different names: land for peace; two-state solution; end the occupation; land division, etc. Philosopher Thomas Kuhn suggested signs that a paradigm has lost its validity: when experiments begin to yield results that don’t support the paradigm, and when it no longer provides a reasonable explanation for the questions and contradictions within it. That is how crisis begins. During crisis, various ideas emerge until one of them leads to a paradigm shift and ultimately to a revolution of thought. Kuhn compared the paradigm shift among scientists to religious conversion. To borrow Kuhn’s religious conversion comparison, those who continue to push for the old peace agreement paradigm at the exclusion of all other ideas become infuriated with fellow supporters who change their minds. Anyone who no longer believes in the old theory is immediately labeled an “infidel” and accused of destroying any chance of peace.

The old paradigm has existed since the day after the Six-Day War. Its underlying premise has always been that peace can be achieved if conquered territory is returned. This was the basis for the Oslo Accords. But all efforts to implement this paradigm with the Palestinians have failed. Every withdrawal resulted in war or conflict. It failed to ignite any talk of peace among the Palestinians. Even if we believe that, as the Left insists, there is no existential danger in withdrawing from strategic territory in favor of a Palestinian state, the question remains: Who said that the Palestinians are interested even in the most generous of compromises? They have refused our offers for a hundred years. Why should they agree now to a small state in the place of the large geographical territory they claim was stolen from them by the Jews? We’ve adopted a strange habit of bearing in mind our enemies’ considerations for them and then being surprised when they don’t live up to our expectations.

5.

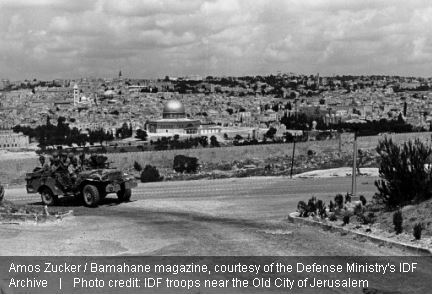

Not only are we projecting our own aspirations and dreams onto the Arabs, we are ignoring the Jerusalem issue — the bone of contention in this conflict. Zionism gets its name from Zion, which is Jerusalem. Not merely as a religious or spiritual symbol, but as a national, geographic objective as well. Would we have remained a nation without our collective pledge never to forget Jerusalem? Doubtful. What erupted in our national consciousness when the Old City of Jerusalem was liberated in 1967 cannot be undone. It cannot be stuffed back into a bottle for “rational” reasons of demographic threats and loss of democracy and other such arguments. We pledged our loyalty to this city for 2,000 years in exile, and no one can convince us that we need to give it (or some of it) to our enemies “for the sake of our future,” because it is the only way to achieve peace. Seriously? Can the Jewish people forge an independent national identity without the religious infrastructure drawn from our scriptures, our traditions, our values and our ideas? Did anyone think that after returning to this holiest of places, we would be willing to give it up in exchange for promises of peace? What good is peace if Jerusalem is divided again, or if a foreign flag flies over it? Do we not run the risk of destroying the Zionist spirit and the will to fight for our existence if we consciously relinquish Jerusalem? And if we do relinquish it, will that not constitute a far greater existential threat than the demographic boogeyman?

The “land for peace” paradigm is therefore wrong, and it imperils us all. Clinging to it prevents us from building the Iron Wall — that wall of deterrence that Zeev Jabotinsky talked about at the start of the 20th century — in the minds of the Arabs around us. As long as they keep hearing meaningless talk of a “two-state solution”, a “one-time window of opportunity” and that “Israel is in danger” they will continue to cultivate a childish hope that, given the daily cost of holding on to the land of their forefathers, the Jews will ultimately give up and leave.

6.

Fifty years after the war, 70 years after the U.N.’s Partition Plan and 100 years after the Balfour Declaration (and 120 years after the First Zionist Congress), the conflict is still being handled as if the language that we use to describe reality is shared by both sides. Peace, territory, occupation, morality, time (history), state, solution, war, etc. When France and England concluded the Hundred Years’ War, or when German and France signed a peace agreement, they shared cultural and religious characteristics, regardless of the differences between the Catholic, Protestant and Anglican churches. The figures featured in Plato’s dialogues also shared a common language, culture and set of values. Most importantly, they operated within the same realm of meaning.

Among other things, perception of reality is derived from cultural perception. Western culture was common to all the players in the historical drama in Europe. The concept of “solution” was agreed upon by all. The history of Western philosophy is paved with questions of perception and “truth.” That didn’t prevent the West from looking at reality in a logical, rational manner. From Aristotle to David Hume, the idea of cause and effect has shaped the view of reality. Every phenomenon is caused by something. If we understand the reason, we can resolve the problem.

This way of thinking may be true for Europe, but in the Middle East, the culture, the history, the religion and the mythology shape reality in a different way. Here, not every problem has a clear reason. And even if it does, it is not always possible to use it to solve the problem. Many times, people assume that a problem will resolve itself in time — sometimes a year, and sometimes a thousand years. The concept of time is different here than it is in the West, hence the differing understanding of history. The term “solution” (as in “two-state solution”) may sound pleasant to Western ears, but it is all but meaningless in the Middle East, unless one seeks to impress Western visitors.

7.

This dual system of two parallel cultures that never actually meet has been shaping the conflict since its onset. The negotiators use the English word “territories” but does the word mean the same thing to both sides?

For the Israeli diplomat, raised on the culture of the West, territories are swathes of land that can be traded for precious peace. If you view the conflict as territorial, logic suggests that sharing the territory would resolve the conflict. The Arab representative, however, refers to “territory” in its ancient cultural sense — land. Like in the Bible. In Hebrew, the word man (adam) is derived from the word land (adama). In other words, a man without land is not a man. His right to exist comes into question and he becomes ready to spill blood (dam in Hebrew — also derived from the same word) to defend the land that defines his existence. If you view the conflict in this context, compromise becomes highly unlikely. Certainly when the conflict is between tribes or nations and even more so when the conflict is religious, which adds another aspect of sanctity to the equation.

8.

In Western discourse today, occupation is a crime. Invading someone else’s territory and imposing foreign rule over the natives is a crime. Ironically, Islam is very familiar with this method — it is how it became the second largest religion in the world. Traditionally, Jews living in Muslim countries have had a status of docile, conquered dhimmis (protected persons). In Jordan, no one talks about “occupation” even though 80% of the Palestinians there are governed by the Hashemite minority hailing from the Arabian Peninsula. In Syria there was also no talk of “occupation” even though the Alawite minority ruled over the Sunni majority and other ethnicities.

The word “occupation” is only used in reference to Israel. No matter what it does, it will always be seen as an occupier. In the summer of 2005, Israel withdrew completely from the Gaza Strip. When it became apparent that the Gazans had chosen Hamas and begun to store weapons — weapons that would be used against Israel — Israeli authorities had to impose a blockade and inspect incoming goods. That was enough to convince the world that we are still occupiers.

In the Palestinian Authority, the Palestinians have their own government, their own anthem, their own flag, their own parliament and their own budgets. There are some restrictions on movement due to security reasons — ones that the Palestinians themselves are responsible for exacerbating. In any case, Israeli presence there in no way resembles the “occupation” of the pre-Oslo Accords era.

Within the borders of tiny Israel, Israeli Arabs who enjoy full civil rights also think of themselves as living under “occupation.” The position paper compiled by the Higher Arab Monitoring Committee characterizes Israel as the product of a colonialist plot that forced them into citizenship in a Jewish state. They do not identify with Israel’s symbols or its national ethos. Despite having the right to vote in Israel, they still view themselves as living under occupation.

Here, in Israel, occupation is a defined term. The other side, however, expands this definition ad absurdum. Any control by non-Muslims over Muslims is a disgrace, deriving from Islam’s belief that it is superior to all other religions and nations. But the world thinks that they are talking about a fight against “occupation.” To the region’s Muslims and Arabs, the very existence of a Jewish state in the Middle East is deplorable. Remember that aforementioned single Jewish neighborhood in Tel Aviv? The one we wanted just one Arab leader to recognize? Even if millions of Jews inhabited that neighborhood, it would still be defined as under “occupation.”

When Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas talks about a “just peace” or a “courageous peace,” he is not talking about the 1967 occupation. Try to find one Arab leader who thinks the occupation started in 1967. Most Arabs will tell you that it began in 1948, when Israel was established, and the rest will say it started at the end of World War I or, even earlier, with the first Zionist immigrations. Listen to the speeches, read the textbooks, watch the media, look at the clerics in the mosques, read the Hamas charter or the Fatah charter or the Israeli Arab policy paper — “just peace” means erasing Israel from the map in one way or another. That is the only justice they will accept.

9.

We do not need the region’s Arabs or the nations of the world to approve of our existence in this land. The Jewish people have returned to their national homeland, first and foremost, to these tracts of land, to Samaria, Judea and especially Jerusalem. A people cannot be an occupier in their homeland.

The Arab discourse (and that of the radical Left all over the world) tends to compare us to the Crusaders who invaded at the end of the 11th century and imposed their rule for about 200 years. The historical truth is that foreign Muslim invaders also came here, in the seventh century, and forced their religion and their language on the indigenous peoples. Despite their presence, this land was never a Muslim center. It was only defined as an independent national entity when it was Jewish, both then and now.

10.

There are no magic solutions. The choice is not between two future options. We inherited this land from our forefathers. Others, who also claim ownership of this land, tell a different story. Confronting their narrative is part of the war over this land. It has been 50 years since we returned to the places that we had dreamed of during our slumber in exile. What is 50 years in the context of such a long history? Are we worse off today than we were on the eve of the establishment of Israel? Recall the 1940s — the first half of the decade was horrific but the state of Israel was established in the second half.

We are willing to wait another 50 years, even 70 years. A wave of a million new immigrants is headed to Israel in the near future, and the fertility rate among traditional and secular Jews in Israel is on the rise. Our demography is about to change. The geography of the region is also bound to change as massive shifts emerge before our eyes. Europe is also likely to change due to mass migration of the region’s peoples.

We can leave something for future generations to deal with. If there is anything we’ve learned in the thousands of years since our inception as a people it is humility in the face of history and patience. There were only a few instances in which we were called upon to actively decide — like the declaration of independence for example. During most of our existence we conducted ourselves slowly through the treacherous progression of generations, waiting for natural processes to take their course. We learned to beware of false prophets who claim the end is near and promise instant redemption or peace now. As Psalms 116 tells us, “I said in my haste: ‘All men are liars.'” It is not just patience that we need now, but also faith. If we know where we came from, we will know where we are going.